THE LAKE CHAMPLAIN FIRE

Contributed by: Fred McGunagle

It was the morning of 3 July 1957, and we had just finished two weeks of Carrier Ops in the Mediterranean. “Carrier Ops” meant following the carrier and fishing out any pilots who went in the drink.

It was the morning of 3 July 1957, and we had just finished two weeks of Carrier Ops in the Mediterranean. “Carrier Ops” meant following the carrier and fishing out any pilots who went in the drink.

DESRON 8 was scheduled for nine days in Marseilles, France. The LAKE CHAMPLAIN (CVA 39) had already entered the harbor and berthed. We were at Special Sea Detail, so I was on the bridge as the captain’s talker.

I don’t remember the CHAMPLAIN’s radio call, but suddenly over the radio in the pilot house, where people always spoke calmly, came an excited shout: “Teaball, the [LAKE CHAMPLAIN’s call name] is on fire!”

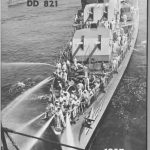

I turned, and a few hundred yards across the harbor thick black smoke was boiling up out of the carrier’s stern and rising hundreds of feet into the air in a plume that kept going higher. I don’t know if we asked if they needed assistance or they radioed us first, but we were asked to go over and hose down their port side to cool the magazine. We put our bow a few feet away and played hoses on the hull – somewhat nervously at first, because only a few feet and the thickness of the LAKE CHAMPLAIN’s hull separated us from the ordnance that threatened to provide Fourth of July fireworks a day early.

We were secured after 20 or 30 minutes and proceeded to dock. The citizens, by the way, were less than thrilled. Marseilles had elected a Communist mayor and the Frenchmen on the “Can o’ beer” (Rue Canobiere) showed what they thought of Americans by spitting in our direction when we walked by.

Two weeks later, when we got into Valencia, I received a dozen or more back issues of the Cleveland Press, for which I had worked before I was drafted in 1955. The banner head in the July 3 city edition was to the effect that “CARRIER EXPLOSION IN FRANCE KILLS U.S. SAILORS.” I hadn’t known the casualty count. The story said three sailors and a French dock worker died when a launch into which they were offloading vehicles caught fire, presumably from spilled gasoline. We got a mention: “Firefighters from the U.S. destroyers aided the French fireboats.

I made a printout of the front page, but the only edition on microfilm was the home edition, and in that the fire had yielded to a Kremlin shakeup as the play story. It was still on Page One, albeit under a one-column head, and I reproduced it. I had forgotten the part about arriving at 3 a.m., but I’m pretty sure we stood outside the harbor until daylight.

It also seems that somebody on the LAKE CHAMPLAIN – I assume a JO (journalist) — got a picture from the carrier deck of us squirting water and just about the whole crew except the snipes standing on deck watching. We used it as the title page of our Med cruise book.

For the benefit of crew members from other eras, the other ships in the squadron at this time were the USS JOSEPH P. KENNEDY JR. (DD 850) (named after the brother of the future president), USS PERRY (DD 865) and USS WARE (844). Our radio call was “Teaball,” and COMDESRON 8, who had his flag on the KENNEDY, was “Chariot GOLF. The WARE was “Wireworm” — “Teaball, Teaball, this is Wireworm.” (I’m sure you remember that GOLF was, as of 1956, the seventh letter of the International Pronouncing Alphabet we learned in boot camp. I can still signal ALFA-BRAVO-CHARLEY-DELTA-ECHO-FOXTROT-GOLF, but when I get to HOTEL-INDIA-JULIET-KILO you have to use both arms and I’ve forgotten.)

I was the co-editor, with Hal Rosenthal, of our cruise book, and with the indulgence of the webmaster I’d like to quote what I wrote on the last page, because it holds up pretty well:

With time, the details of the cruise will fade, leaving only memories, different with every person, because everybody chooses among thousands of impressions, good and bad, the ones he wants to remember.

But most people, being optimists in spite of themselves, will with the years forget the disagreeable part: reveille, and stew, and water hours, and chow lines, and all the irritations that people cause other people because they want to show their authority, or because somebody else gave them a hard time, or maybe simply because it’s been a long cruise for them too.

And the things that remain will be: the black shadow of the mast slowly rocking across a sky of stars; and the sun setting gold and purple on the sea while the IC men wait to start the movie; and coming back to the ship, pleasantly shot down after an evening of wandering around town with the boys; and mail call, and rack time, and coming home, of course; but most of all just the guys, 279 of them counting officers (officers are guys too, deep down), who worked and loafed and ate and slept and wrote letters and sweated inspections and lived with you on the same 400-foot hunk of tin that was home.

And so, this book is dedicated to those 279 guys, in the hope that, in five or ten years, when life aboard the Johnston seems as hard to remember as life anywhere else seems now, they may look through it and say, “Oh, yeah, remember that bar in Palma?” or “I wonder whatever happened to old So-and-so,” or even “We didn’t have such a bad time then after all,” which, when you come right down to it, is about as much as you can say about life.

It wasn’t what I wanted to be doing at the time, but, 47 years later, I’ve got to say it: We didn’t have such a bad time then after all.